Pigskin Dispatch’s Part 4 in the Series on American Football History

Football transforms from its Ancient European roots. Recap.

When we last visited this series, a new game called rugby was shipped across the sea to America from England. Rugby was a brutal game, and many schools in England decided not to play it and instead chose association football, or soccer. The soccer name obviously stayed here in the States, but in Great Britain, as well as much of the world, soccer is called football.

America transforms the game.

Rugby is the sport that became popular early in America. By 1860, the game was abolished in many American schools due to its rough nature. It was revived in 1862 by Gerritt Smith Hiller, who organized a group of Yale students to play again, using rules that were a reasonably close imitation of soccer. Still, the game was often more an excuse to beat up first-year students in a hazing activity than anything else.

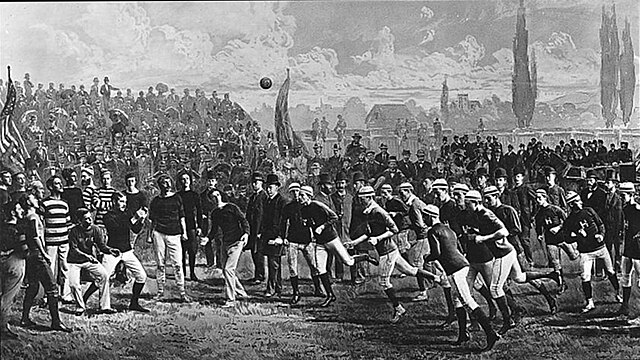

The game stuck around and became popular at the eastern colleges, though, and on November 6, 1869, an inter-collegiate match was played between Princeton and Rutgers. The game played this day was very similar to rugby, with twenty players on the field for each team during the action.

In 1871, Harvard University began playing a variation of the game called “the Boston Game,” which differed from the others by allowing a player to pick up the ball and run if he was chased.

In the fall of 1873, Yale invited representatives from Harvard, Rutgers, Columbia, and Princeton to a convention in New York City to draft rules for an intercollegiate football association. ( a precursor to the NCAA) Harvard declined to attend because the other schools had no intention of honoring any of the rules of the Boston game. The four remaining schools established the Intercollegiate Football Association (IFA) and set 15 as the maximum number of players per team.

Harvard players still had a strong desire to play other schools, so in 1874, Harvard challenged Yale to a game under the Boston rules. Yale declined the challenge due to rule differences, as the match played under IFA rules was more similar to soccer. Harvard’s team captain, Henry Grant, was still not discouraged. He was anxious for his football team to compete and had heard that a similar game was played just over the Canadian border at McGill University. Consequently, Grant got in touch with the captain of the McGill team, David Roger, and invited them to play two games in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on May 13 and 14, 1874.

Harvard, until this time, was still playing the Boston game, and the rules also resembled soccer more than today’s game of American football. The Boston rules differed from the IFA version, though, because in the IFA, a player could never pick up the ball and run. Boston rules allowed him to pick it up and tuck it only when an opponent was chasing him. Harvard players were in for a surprise when the McGill squad came to Cambridge a few days early and practiced in front of them. The McGill players kicked the ball and subsequently ran with it under their arms. Harvard’s Grant pointed out politely that this violated a basic rule of American football. The McGill captain replied that it did not violate any rule of the Canadian game. When the Harvard captain asked the McGill leader, “What game do you play?” David Roger replied, “Rugby.” They then agreed to play the forthcoming games under half-Canadian, half-American rules. Harvard typically played with 15 players to a side, but McGill could only bring 11 to the contests, so both sides used an 11-on-11 format.

Canadians Help Start American Football

The Harvard University newspaper printed the following excerpt the next day: “The McGill University Football Club will meet the Harvard Football Club on Wednesday and Thursday, May 13th and 14th. The game will probably be called at 3 o’clock. Admittance 50 cents. The proceeds will be donated to the entertainment of our visitors from Montreal.”

The May 13 contest started with the Canadian colleges’ rules and was to have the second half be the Boston rules. Harvard players enjoyed the Montreal version so much that they requested their opponents to play the remainder of the game with the rules McGill brought. Harvard won the first game 3-0. The next day’s game ended in a scoreless tie between the two schools. Harvard adopted many elements from the game their Canadian friends had shown them, including tackling, downs, and field goals.

These changes to Harvard’s football rules were setting the table for something much bigger and better, though. When we resume in part 5 of this series, we will introduce the true mastermind and founder of American football, Walter Camp, and his gang over at the Yale campus in “A New Authoritative Organizational Body and Leader for Football.” Right here on PigskinDispatch.com, your place for the good football news.

We can give this in-depth look into history from so long ago through careful research. Using someone contemporary to the period is the best source. So, a very special shout-out to our primary source of reference for this article: Parke H. Davis, in his 1911 book, Football-The American Intercollegiate Game.