The formations and plays that were winning ballgames were causing injury, and the press sensationalized them so much, that public outcry for change was gaining momentum.

Injury numbers climb

Injury counts trend upward

The Football Rough and Tumble Continues

Pigskin Dispatch's Part 16 in the Series on American Football History

It has been said for a long time that “innovation is the mother of invention.” That may be true in a lot of cases but the innovation in 1893 had some by-products that were probably not all that desirable to football players. Part 15 enlightened the reader to the strategies developed by men like Lorin F. DeLand of Harvard and George W. Woodruff of Yale. These strategies had a lot to do with finding advantages by taking a mass of men and trying to steamroll a certain point in an opposition’s defense.

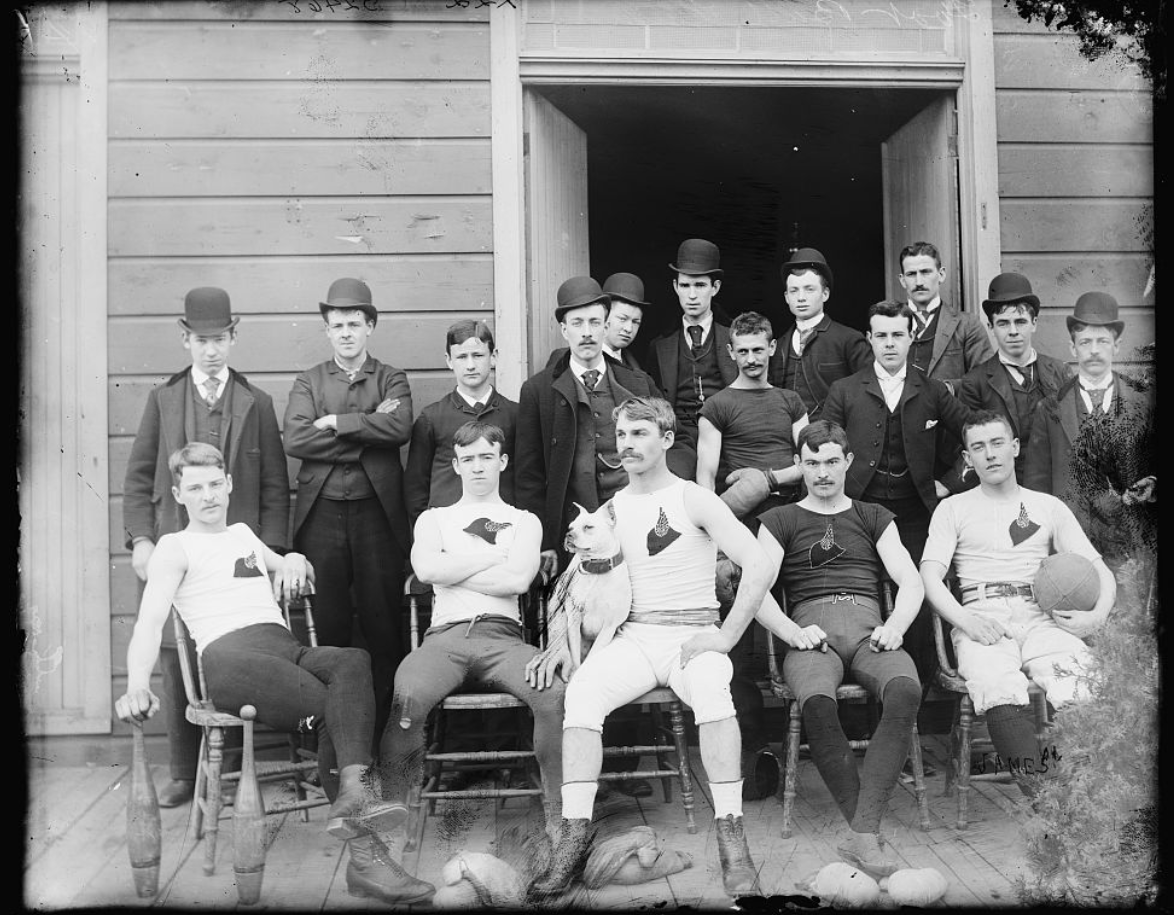

An unknown 1895 Detroit, Michigan area team from the Detroit Publishing Company photograph collection of the U.S. Library of Congress

Football Injury Reports

The game formations and strategies were leading to situations that the human body could not physically tolerate. Writer Parke H. Davis in his 1911 book Football-The American Intercollegiate Game illustrated the point very explicitly when he wrote “the generals had devised plays too powerful for their sturdy soldiers to execute and withstand.”

Davis also suggests that some of the reports of injury may have been exaggerated especially by members of the European press. Davis’s book points out one such article in the Munchener Nachrichten (a German periodical) that reported a story on the November 1893 meeting between Harvard and Yale (see Part 15 of this series) that sounded more like a battle account in a war then a game played by collegians.

”The football tournament between the teams of Harvard and Yale, recently held in America, had terrible results. It turned into an awful butchery. Of twenty-two participants seven were so severely injured that they had to be carried from the field in a dying condition. One player had his back broken, another lost an eye, and a third lost a leg. Both teams appeared on the field with a crowd of ambulances, surgeons and nurses. Many ladies fainted at the awful cries of the injured players. The indignation of the spectators was powerful, but they were so terrorized that they were afraid to leave the field.” (Writers note: Remember these are the Germans writing this piece, the future instigators of two world wars and a horrific holocaust.)

Davis eludes that articles like this popped up in tabloids and fish wraps alike around the world but he felt to certain extent the reports reeked of sensationalism used to sell papers. They did have influence though as public outcry became very apparent in the late 1890’s and on into the early twentieth century. The Secretary of the Navy and Secretary of War abolished the upcoming Army-Navy series by restricting members of both Academies to their own campuses.

Part of the reason for the reactions of the public was that there was no authoritative council for football rules in place any more. The once powerful Intercollegiate Association had dwindled over the years to have two members left, Princeton and Yale. The other schools had left the Association mainly due to player eligibility disputes and the like. Something had to be done to save this game! Someone needed to rise up and stop the tail spin! The game could die out soon if corrections were not made soon that would reduce injury and unite all teams and leagues into common rules that would appease a worried public.

How to tame the beast that football had become?

The University Athletic Club of New York called for members of Princeton, Pennsylvania, Harvard and Yale to come together and assume authority over all football rules to try and tame the “beast” it had become. The four schools immediately accepted the assignment and they scrambled to elect their respective representatives to the newly formed body. The representatives selected were W.A. Brooks, J.C. Bell, Alexander Moffat and Walter Camp. This group of men decided to make it a five-some as they also invited the foremost official of the time, Mr. P. J. Dashiell, to join them to get his perspective and influence into the reformation of the great game.

Before the group had even met Walter Camp sent out a survey to every known former football player in the United States requesting answers for specific questions on the injury plague that had bitten the game. The response by the former players was overwhelming and Camp categorized the answers and published them. The results showed that many of the stories were unfounded and very much exaggerated. This report from Camp’s investigation made the accusations of outsiders subside almost to the point of non-existence on the horrific injuries.

The group of five then had many meetings in 1894 to come up with a plan to change the game so that the injuries that did occur could be greatly reduced. The investigation of Camp had shown that most former players felt that the mass momentum plays including the “V” and the “Flying Wedge” formations were the main items that produced injury. The results of these early sessions saw the group abolish the V-formation as well as the flying wedge and they restored the concept of the old-style kick-off. They took care of the mass momentum offensive plays by banning the grouping of players more than five yards behind the line, thus reducing the amount of momentum they could produce before they hit the line. The rules revisions were the most radical and widespread changes the game had seen since those of 1882.

They did not satisfy the public yet though as it was felt there were more ills to the game than just a couple of formations. We will further discuss the happenings in football in this situation in Part 17 so please look back soon. Right here on PigskinDispatch.com, your place for the good news about football.

We are able to give this in depth look from so long ago in history by careful research. Using someone who was contemporary to the period is the best source. So a very special shout out to our main source of reference information for this article is from Parke H. Davis in his 1911 book Football-The American Intercollegiate Game.