In this edition of the Football History Rewind, we discuss early football development from 1874 to 1882, along with some legendary stories than commenced.

Football 1874 to 1882

1870 to 1873 Schools That Started Football Programs

The year 1873 witnessed the formation of several independent football programs, each contributing to the nascent stages of American football's development. These institutions, unbound by conference affiliations, forged their paths in shaping the sport. The Harvard Crimson, a future powerhouse, began its gridiron journey, laying the groundwork for its storied tradition. Further south, the Washington & Lee Generals embraced the burgeoning sport, establishing a program to cultivate generations of scholar-athletes. Across the border, the McGill Redmen, playing a form of rugby football, introduced innovative tactics that would influence the American game.

Beyond collegiate ranks, Eton, the prestigious English boarding school, also fielded a team, showcasing the sport's growing global appeal. The CCNY Lavender and NYU Violets joined the football fray in New York City, representing the city's expanding athletic landscape. Virginia Military Institute (VMI), emphasizing discipline and teamwork, established the Keydets program, instilling values that would translate onto the football field. While focused on theological studies, Princeton Seminary also recognized the value of sport, creating a team that would compete against other local clubs and schools. Finally, the New Jersey Athletic Club, a prominent athletic organization, embraced football, demonstrating the sport's growing popularity beyond academic institutions and into the broader community. These diverse programs, established in 1873, collectively represent a pivotal moment in the evolution of American football.

The Colorful Nicknames and Traditions of Early Football

In the early days of college football, teams often lacked official nicknames, but the colors of their uniforms provided a natural source of identity. This was particularly true in the East, where the sport first took root.

Harvard's crimson, for example, led to the team being known as the "Crimson," while Yale's blue spawned the "Blue" or "Bulldogs." These simple, color-based nicknames were easily remembered and quickly caught on with fans.

Over time, some schools adopted more distinctive nicknames, often inspired by animals or historical figures. But the connection to uniform colors remained strong. Princeton's orange and black, for instance, contributed to their "Tigers" moniker.

This trend of color-based nicknames wasn't unique to the Ivy League. Across the country, teams like the "Crimson Tide" of Alabama and the "Longhorns" of Texas emerged, their identities inextricably linked to their colors.

While some nicknames evolved, the early practice of using uniform colors as a basis for team identity remains a fascinating glimpse into the evolution of college football.

These nicknames, often born from the colors on their backs, added a layer of personality and tradition to college football. They became rallying cries for fans and symbols of pride for players, solidifying their place in the sport's rich tapestry.

Football 1874 A New Authority Arises

A New Authoritative Organizational Body and Leader for Football

Pigskin Dispatch's Part 5 in the Series on American Football History

A Princeton influence on the game

It would be a travesty if this blog failed to mention that in the 1820’s a group of students at Princeton began playing what was then known as ‘ballown’. This game used an oval shaped bladder filled ball and the rules transformed as time went along. At first players used their fists to advance the ball, and then their feet, this game consisted mainly of one goal: to advance the ball past the opposing team.

From Parke H. Davis book Foot ball: The Intercollegiate Game.

The IFA and Harvard rules collide

In 1875 Harvard again challenged Yale to a game only this time they agreed to play a combination of soccer and rugby rules, much like McGill had played in 1874. Yale agreed to these rules but they included the use of a round ball rather than the oval one Harvard normally used. Harvard won this game of agreements versus rival Yale in front of 2000 fans. The spectators and players from both schools loved the game and decided to make it an annual event.

According to author Timothy Brown in his book How Football Became Football, students from Harvard, Columbia, Yale and Princeton met in 1876 to define what the rules of this game were that they were all interested in playing against each other. The group called themselves the Intercollegiate Football Association or IFA. It was at one of these early meetings Brown tells us that the critical decision of which rules to follow were discussed. Should they choose the Association rules or those of Rugby. The Harvard contingent put a most compelling case together and the rugby rules won out.

The 1876 meeting put together a set of 61 different rules to define this version of football. Most of them were an exact copy of the English Rugby Union set of guidelines. How Football Became Football, once again tells us the differences of the IFA rules from the ERU:

- A referee and two umpires, supplied one each from each team, were settle disputes ratehr than the team captains as in the ERU code.

- Touching the ball down in an opponents goal was called a touchdown and not a try as in the ERU code.

- The winner was the team that scored the highest number of touchdowns rather than the highst number of kicked goals.

- There were standard field dimensions for IFA games rather than a maximum size playing surface.

Timothy Brown sates that the rule of 1876 are confusing to us today partly because of the terminology of that era was so much different than what things are called today and that there were so many revisions to the rules in the past 140 some odd years. He says that only 3 of the 61 rules of 1876 are basically unchanged in the modern game. Many of those rules tweaks were to come from one innovator of the game.

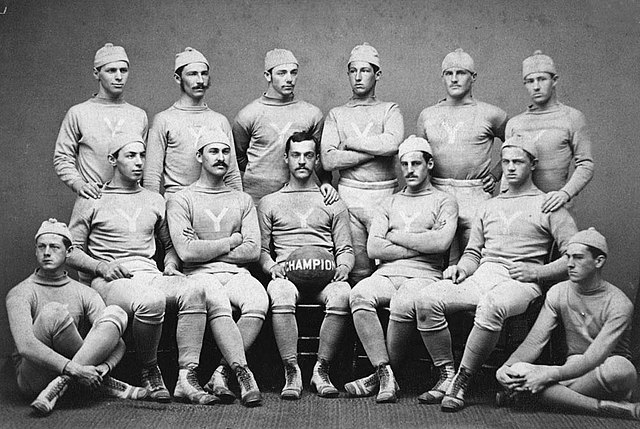

Yale Bulldogs football team. Left to right, back row: Clark, C. Camp, Hatch, W. Camp, Wurts, Taylor. front row: Davis, Downer, Walker, Baker, Bigelow, Thompson, Morse Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

During the next few years though a new figure entered the Yale football scene, yes you guessed it, Walter Chauncey Camp. Walter Camp arrived at the New Haven campus in 1876 and enjoyed the game that the Yale and Harvard clubs were playing. Camp so loved the sport he joined the Yale team in 1877 and basically became its first head coach. as at the time the label of Captain served as the role. Camp not only coached the team he was a player too. He played on the varsity teams of Yale from 1877 to 1882, serving as Captain in 1878, 1879, and again in 1881. Camp’s leadership gave Yale 25 wins, one loss and 6 ties over his playing career. He was a sure tackler, a great kicker and an elusive runner. Camp attended the 1878 IFA rules meeting and may have been there in 1876 as well.

Courtesy Wikimedia.com

Camp though as great of a player he might have been is not famous for his feats as a football athlete, but is the main innovator that changed rugby into American football. It started in 1882 after his playing career was over and his term of serving on the IFA rule committee started.

The story of Camp the innovator will be in the next installment of this football history expose in part 6 titled, “Settling the Score in Football." Right here on PigskinDispatch.com, your place for the good news about football.

We are able to give this in depth look from so long ago in history by careful research. Using someone who was contemporary to the period is the best source. So a very special shout out to our main source of reference information for this article is from Parke H. Davis in his 1911 book Football-The American Intercollegiate Game.

1879 More Schools Join In

1879 established several independent football programs, each contributing to the sport's growth. The Michigan Wolverines, destined for national prominence, began their football journey, laying the foundation for their storied legacy. The Massachusetts Aggies (later UMass Amherst) also joined the gridiron ranks, fostering a tradition of collegiate athletics.

Haverford College, emphasizing academics and character, embraced the sport, establishing the Fords program, which would compete for nearly a century. The United States Naval Academy, recognizing the value of physical fitness and teamwork, launched the Navy Midshipmen football program, instilling discipline and leadership in its players. Pennsylvania Military College (now Widener University) also fielded a team, emphasizing the sport's growing appeal beyond traditional Ivy League institutions.

Racine College, a small liberal arts school in Wisconsin, added football to its athletic offerings, demonstrating the sport's spread nationwide. Finally, the University of Toronto, across the border in Canada, established a football team, further highlighting the sport's growing popularity beyond the United States and the interconnectedness of early football development. These independent programs, established in 1879, collectively represent a significant step in the expansion and diversification of American football.